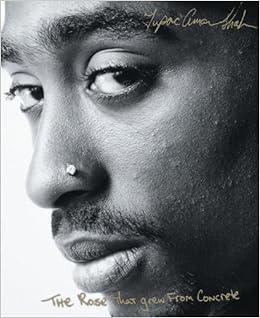

Image from amazon.com

Bibliography

Giles, Gail. Girls

Like Us. Somerville: Candlewick Press, 2014. ISBN: 978-0763662677.

Summary

Biddy and Quincy are self-proclaimed “speddies,” or students

enrolled in a special education program.

Academic challenges aside, these ladies are street-wise; they know the

origins of their respective disabilities, and how the world perceives them

because of them. Upon graduation, their counselor pairs them as roommates and secures

jobs and lodging on the property of a politician’s elderly wife so that they

can live semi-independently in the “real world.” As part of the arrangement, Biddy cleans, and

Quincy cooks and works part-time at the Brown Cow Market. Both young women have suffered unspeakable

violence and ridicule because of their handicaps. When the demons of the past and new monsters

in the outside world threaten to ruin their newfound happiness, they support

each other, pooling their strengths to discover friendship, resilience, and

mutual understanding.

Critical Analysis

Girls Like Us

teaches tolerance for differences.

Because young adults will undoubtedly encounter people from various

walks of life in secondary school, college, and beyond, this is a virtue that

they will do well to acquire. Biddy and

Quincy acknowledge right away that they are differently abled. They know their impediments well, but view them as only one part of their experiences, not the sum of who they

are. The girls are also aware that

people can be cruel about said differences.

They recount being mocked and mistreated by peers, strangers, and their

own families. Biddy and Quincy’s ordeals will engender empathy in their

audience. Giles gives a voice to the

victims of bullying. Teens, who can be

cruel and judgmental, will see that all people are deserving of kindness and

respect.

Girls urges young adults to be open-minded when

contemplating new friendships. Often, we can find humor, strength,

talent, and beauty in the people and places we least expect. Initially,

Quincy looks down on Biddy because the latter is illiterate, and her mental

impairments are more severe. She also labels Biddy promiscuous based on rumors

she hears at school. Biddy puzzles over Quincy's abrasiveness and writes

it off as a feature of her personality, without really exploring the source of

her anger. Naively, Biddy believes that Elizabeth is every bit as kind

and graceful as Quincy is mean. Quincy, however, is wary of her elder, White

employer - she assumes Elizabeth's philanthropy is rooted in pity. Elizabeth is

mostly gracious to the girls, but underestimates and oversteps at times. The

roommates discover that Liz has her own insecurities, that being abled and

wealthy does not guarantee wholeness. When the ladies relax their

suspicions and assumptions, they become a tremendous support to one

another. They instill courage, self-respect, and dignity each

other. They provide comfort and protection. They share their

skills and strengths. Most importantly, each helps to navigate through the

other’s personal traumas. This book encourages teens to develop

authentic, deep friendships, and to rely on those in their circles for water, shade, and

pruning, so to speak.

Finally, this novel addresses the heartbreaking epidemic of

sexual abuse. Unfortunately, women are especially vulnerable, regardless

of age, orientation, socioeconomic status, or ability. Girls is a

timely read for adolescents at an age where parties and dating could

potentially put them at risk. It also reassures victims that they cannot

do anything to provoke, nor are they at fault for violence committed against

them. It also encourages them to report rape, and to depend on a

support system rather than dealing with the hurt alone.

Girls Like Us has a place in young adult literature.

There is a misconception that teenagers have unlimited health and vigor.

Quite the contrary, more than 1.2 million young adults are affected by

disabilities that impede their daily lives. 44% of rape victims are under

18, and more than likely, perpetrators will not face legal consequences for

their crimes. These young people need a voice, and those around them need

to hear and empathize with it. This novel facilitates these goals.

Awards

- 2015 Schneider Family Book Award Winner, Teen

- YALSA’s 2015 Best Fiction for Young Adults

- 2014 National Book Awards Longlist for Young People’s Literature

- Booklist Editors’ Choice 2014

Published Reviews

Henley, Juli. Rev. of

the book Girls Like Us, by Gail

Giles. Voices of Youth Advocates (Voya) 1 Jun. 2014. Web.

Accessed August 13, 2015.

Extension Activities

- The World Through My Eyes – Can you imagine how hard it would be in class if you could not seem to focus, if the letters on the pages just did not make sense, if you could not get the numbers to add up? Go tohttps://www.understood.org/en/tools/through-your-childs-eyes and pick at least two simulations to experience what life is like for people with learning disabilities. Watch the accompanying videos of kids describing their challenges.

- Mama Duck - Biddy has stuffed her abuse deep down into her psyche, convinced that no one values her life enough to take action against her attackers. She rescues Quincy and accompanies her to the police station, but who will be her Mama Duck? Write an alternate ending/addendum in which Biddy takes her agency back. For instance, maybe she cuts up her coat or confronts her grandmother.

- Two Faced - Despite her tough girl exterior, Quincy is insecure about her facial deformity. The reader discovers that she is extremely talented, efficient, intelligent, and strong. Draw and color a picture of how you envision Quincy's face. Make sure that one side is unaffected, and the other reflects her childhood injury. On the unaffected side, cut and paste words that describe her strengths. On the injured half, cut and paste words that reveal her weaknesses. This is a lesson that true beauty lies in our goodness, not our appearance.

Related Literature

- Erskine, Kathryn. Mockingbird. New York: Philomel Books, 2010. Print. ISBN: 978-0399252648 – 10-year-old Caitlin sees things in crisp black and white lines. Because she has Asperger’s syndrome, ambiguities like color, facial expressions, social customs, and figures of speech confuse and frustrate her. Her older brother, Devon, was always there to comfort and help her with her awkwardness. When he is killed in a school shooting, Caitlin has to muddle through grief that is only compounded by ASD, with only the dictionary definition of closure and Devin’s half-finished project as her guides.

- McGovern, Cammie. Say What You Will. New York: HarperTeen, 2014. Print. ISBN: 978-0062271105 - 17-year-old Amy lives parallel to her peers because of cerebral palsy. She spends the majority of her time accompanied by adult aides because of her limitations. For her senior year, Amy resolves to form real friendships. When she recruits other students to be her aides, Matthew applies. By helping Amy, Matthew develops social skills and comes to terms with his own OCD, and they forge an unlikely romance.